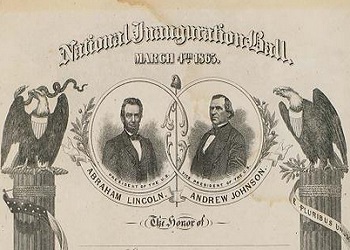

Invitation to Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural ball. This invitation was created by J. Goldsborouh Bruff.

President Lincoln’s second term inauguration took place on March 4, 1865 at the Capitol in the Nation’s Capital. Lincoln read one of the shortest inaugural speeches, only 703 words but it was one of the most memorable. He tried to reconcile differences between Unionists and Confederates and closed his address with the following words:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

After four years he had mastered the difficult job of Chief Executive. He was the only president elected for two consecutive terms since Andrew Jackson in 1832. His administration followed his leadership and commanded the support of both Houses of Congress.

Lincoln was satisfied with his cabinet. The only change was William Pitt Fessenden who was replaced by Hugh McCulloch as Treasury Secretary. Fessenden resigned to take his post in the senate for the state of Maine. Nicolay and Hay, Lincoln’s personal secretaries, received new appointments. Nicolay was offered the US consulate in Paris and Hay received an appointment as secretary of the delegation in Paris.

Free Government

Elections were held during a war and the fact that they were held at all was a sign of Lincoln’s commitment to democracy and freedom.

On November 10, 1864, from a second floor window, President Lincoln addressed a group of serenaders who had gathered outside the White House:

It has long been a grave question whether any government, not too strong for the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its own existence in great emergencies.

On this point the present rebellion brought our republic to a severe test; and a presidential election occurring in regular course during the rebellion added not a little to the strain. If the loyal people, united, were put to the utmost of their strength by the rebellion, must they not fail when divided, and partially paralized (sic), by a political war among themselves?

But the election was a necessity.

We can not have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us. The strife of the election is but human-nature practically applied to the facts of the case. What has occurred in this case, must ever recur in similar cases. Human-nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak, and as strong; as silly and as wise; as bad and good. Let us, therefore, study the incidents of this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be revenged.

But the election, along with its incidental, and undesirable strife, has done good too. It has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election, in the midst of a great civil war. Until now it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. It shows that, even among candidates of the same party, he who is most devoted to the Union, and most opposed to treason, can receive most of the people’s votes. It shows also, to the extent yet known, that we have more men now, than we had when the war began. Gold is good in its place; but living, brave, patriotic men, are better than gold.